‘The Evenings’ by Gerard Reve has been hailed as a “postwar masterpiece” and “the best Dutch novel of all time” but has only recently been translated by Sam Garrett and published in the UK for the first time by Pushkin Press late last year, nearly seven decades after it was first printed in the Netherlands. It tells the story of Frits van Egters, a 23-year-old clerk living with his parents in Amsterdam who struggles to fill his non-working hours with anything meaningful, spending his evenings walking past the canals, seeking out conversation with his small group of friends including his brother Joop.

‘The Evenings’ by Gerard Reve has been hailed as a “postwar masterpiece” and “the best Dutch novel of all time” but has only recently been translated by Sam Garrett and published in the UK for the first time by Pushkin Press late last year, nearly seven decades after it was first printed in the Netherlands. It tells the story of Frits van Egters, a 23-year-old clerk living with his parents in Amsterdam who struggles to fill his non-working hours with anything meaningful, spending his evenings walking past the canals, seeking out conversation with his small group of friends including his brother Joop.

Continue reading

Tag Archives: Translated Fiction

The Evenings by Gerard Reve

Filed under Books

Three Books for Women in Translation Month

As some of you may already know, August is Women in Translation Month (founded by book blogger Meytal at Biblibio in 2014) which aims to increase readership of translated books by female authors and raise awareness of the gender imbalance in publishing (estimates vary but currently only around 25-30% of books translated into English are by female authors). The three titles I have been reading this month from authors based in Israel, Austria and Mexico showcase the variety of fiction written by women around the world and championed by independent publishers Pushkin Press, Peirene Press and Granta.

Waking Lions by Ayelet Gundar-Goshen (translated from the Hebrew by Sondra Silverston) tells the story of Dr Eitan Green, a neurosurgeon who has recently relocated to the Israeli city of Beersheba and is involved in a collision with an illegal Eritrean immigrant while he is driving home from work through the desert. In a panic, Eitan leaves him to die at the side of the road, but the dead man’s widow shows up the next day on his doorstep holding his wallet which he left at the scene and blackmails him into providing medical assistance to other illegal immigrants in the area. To complicate matters even further, Eitan’s wife Liat is the police detective tasked with uncovering the identity of the driver who left the scene of the hit-and-run. Continue reading

Waking Lions by Ayelet Gundar-Goshen (translated from the Hebrew by Sondra Silverston) tells the story of Dr Eitan Green, a neurosurgeon who has recently relocated to the Israeli city of Beersheba and is involved in a collision with an illegal Eritrean immigrant while he is driving home from work through the desert. In a panic, Eitan leaves him to die at the side of the road, but the dead man’s widow shows up the next day on his doorstep holding his wallet which he left at the scene and blackmails him into providing medical assistance to other illegal immigrants in the area. To complicate matters even further, Eitan’s wife Liat is the police detective tasked with uncovering the identity of the driver who left the scene of the hit-and-run. Continue reading

Filed under Books

The Man Booker International Prize Winner 2017

The official winner of the Man Booker International Prize was announced last night with A Horse Walks into a Bar by David Grossman translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen taking the £50,000 prize split equally between author and translator. The novel about a stand-up comedian going into meltdown on stage has been praised by the judges as “an extraordinary story that soars in the hands of a master storyteller” and “a mesmerising meditation on the opposite forces shaping our lives: humour and sorrow, loss and hope, cruelty and compassion, and how even in the darkest hours we find the courage to carry on.” Continue reading

The official winner of the Man Booker International Prize was announced last night with A Horse Walks into a Bar by David Grossman translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen taking the £50,000 prize split equally between author and translator. The novel about a stand-up comedian going into meltdown on stage has been praised by the judges as “an extraordinary story that soars in the hands of a master storyteller” and “a mesmerising meditation on the opposite forces shaping our lives: humour and sorrow, loss and hope, cruelty and compassion, and how even in the darkest hours we find the courage to carry on.” Continue reading

Filed under Books

Man Booker International Prize Reviews: Part 5 (and the shadow panel shortlist)

The Man Booker International Prize shadow panel’s scores are in and we can now announce our own shortlist of six books. They are:

The Man Booker International Prize shadow panel’s scores are in and we can now announce our own shortlist of six books. They are:

- Compass by Mathias Énard (translated from the French by Charlotte Mandell)

- The Unseen by Roy Jacobsen (translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett and Don Shaw)

- Bricks and Mortar by Clemens Meyer (translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire)

- Judas by Amos Oz (translated from the Hebrew by Nicholas de Lange)

- Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin (translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell)

- Fish Have No Feet by Jón Kalman Stefánsson (translated from the Icelandic by Philip Roughton)

There is a fair amount of overlap between our shortlist and the official shortlist with just ‘Bricks and Mortar’ and ‘Fish Have No Feet’ being favoured over ‘Mirror, Shoulder, Signal’ and ‘A Horse Walks Into A Bar’. My personal preferences lean towards the books by Jacobsen, Stefánsson and Schweblin while other shadow panel members have made strong cases in favour of the more avant-garde titles. We will be deliberating our choices this month and announcing our winner in June.

Continue reading

Filed under Books

Man Booker International Reviews: Part 4 (and the official shortlist)

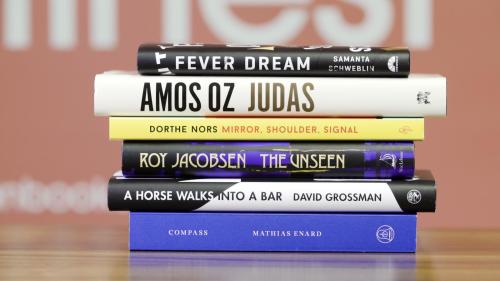

The official Man Booker International Prize shortlist of six books was announced on Thursday:

- Compass by Mathias Enard (translated from the French by Charlotte Mandell)

- A Horse Walks Into a Bar by David Grossman (translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen)

- The Unseen by Roy Jacobsen (translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett and Don Shaw)

- Mirror, Shoulder, Signal by Dorthe Nors (translated from the Danish by Misha Hoekstra)

- Judas by Amos Oz (translated from the Hebrew by Nicholas de Lange)

- Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin (translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell)

I think this is an interesting selection with some very strong contrasts in genre and style. The shadow panel shortlist will be revealed at a later date as we have decided to allow ourselves a bit more time to finish reading the longlist and deliberate our views. You will have to wait until 9am UK time on Thursday 4th May to find out how many of our collective choices match those of the official judges… Continue reading

Filed under Books

Man Booker International Prize Reviews: Part 3

Bricks and Mortar by Clemens Meyer is the biggest of the big tomes on this year’s longlist and I have been reading it in between other books on the longlist over the last three weeks. For that reason, I’m not sure if I felt the full force of its power but as the book is so fragmented anyway, I don’t think I felt any more disorientated each time I picked it up again than I would have done if I had read it straight through without distractions. Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire, it follows a variety of characters involved in the sex trade in an unnamed East German city from the end of the Cold War to the present day exploring the consequences of legalised prostitution, corruption, capitalism, and much much more. Each chapter explores a different character associated in some way with the industry and the chorus of unique voices effectively becomes a collection of interconnected short stories. At the centre of the story is Arnold Kraushaar and his rise “from football hooligan to large-scale landlord and service-provider for prostitutes”. Continue reading

Bricks and Mortar by Clemens Meyer is the biggest of the big tomes on this year’s longlist and I have been reading it in between other books on the longlist over the last three weeks. For that reason, I’m not sure if I felt the full force of its power but as the book is so fragmented anyway, I don’t think I felt any more disorientated each time I picked it up again than I would have done if I had read it straight through without distractions. Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire, it follows a variety of characters involved in the sex trade in an unnamed East German city from the end of the Cold War to the present day exploring the consequences of legalised prostitution, corruption, capitalism, and much much more. Each chapter explores a different character associated in some way with the industry and the chorus of unique voices effectively becomes a collection of interconnected short stories. At the centre of the story is Arnold Kraushaar and his rise “from football hooligan to large-scale landlord and service-provider for prostitutes”. Continue reading

Filed under Books

Man Booker International Prize Reviews: Part 2

My Man Booker International Prize shadowing duties continue with two more reviews this week. First up is War and Turpentine by Stefan Hertmans which has been translated from the Dutch by David McKay. Hertmans inherited his grandfather’s diaries after his death in 1981 and eventually used these personal memoirs to create a compelling narrative of his life as an ironworker, soldier and amateur painter. Born in 1891, the first part of the book focuses on Urbain Martien’s childhood in Ghent in a working class family with his father Franciscus and mother Céline. Hertmans also inserts himself into this part of the story as he unravels his family history in the present day. The second part is a more conventional narrative of Urbain’s experiences in the trenches following the German invasion of Belgium. The final part recounts the post-war years during which Martien sought solace in painting and a secret at the heart of his marriage to Gabrielle is revealed.

My Man Booker International Prize shadowing duties continue with two more reviews this week. First up is War and Turpentine by Stefan Hertmans which has been translated from the Dutch by David McKay. Hertmans inherited his grandfather’s diaries after his death in 1981 and eventually used these personal memoirs to create a compelling narrative of his life as an ironworker, soldier and amateur painter. Born in 1891, the first part of the book focuses on Urbain Martien’s childhood in Ghent in a working class family with his father Franciscus and mother Céline. Hertmans also inserts himself into this part of the story as he unravels his family history in the present day. The second part is a more conventional narrative of Urbain’s experiences in the trenches following the German invasion of Belgium. The final part recounts the post-war years during which Martien sought solace in painting and a secret at the heart of his marriage to Gabrielle is revealed.

Continue reading

Filed under Books

Man Booker International Prize Reviews: Part 1

The shadow panel members have been busy reading the titles longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize. Here are my thoughts about the first four books I have read since the announcement last month:

The shadow panel members have been busy reading the titles longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize. Here are my thoughts about the first four books I have read since the announcement last month:

Yan Lianke’s novel The Four Books was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize last year and was one of the most interesting new discoveries I made last year. Translated from the Chinese by Carlos Rojas, The Explosion Chronicles follows three families – the Kongs, the Zhus and the Chens – who compete to turn their small village into a super metropolis. Lianke’s latest novel to be translated into English is another absurdist satire which criticises corruption, capitalist excess and China’s rapid economic growth with impressive detail and the way in which the story is presented as a history of the town as a sort of miniature account of what has happened to the country in general is done very effectively. Continue reading

Filed under Books

Man Booker International Prize: Shadow Panel Response

Here is our shadow panel response to the Man Booker International Prize longlist announced earlier this week (thanks to Tony for collating our initial thoughts):

The Shadow Panel for the 2017 Man Booker International Prize would like to extend its congratulations and thanks to the official judges for their hard work in whittling down the 126 entries to the thirteen titles making up the longlist. In some ways, it is a somewhat unexpected selection, with several surprising inclusions, albeit more in terms of the lack of fanfare the works have had than of their quality. However, it is another example of the depth of quality in fiction in translation, and it is heartening to see that there is such a wealth of wonderful books making it into our language which even devoted followers of world literature haven’t yet sampled. Of course, at this point we must also thank the fourteen translators who have made this all possible, and we will endeavour to highlight their work over the course of our journey.

Continue reading

Filed under Books

The Man Booker International Prize Longlist 2017

The longlist for the Man Booker International Prize 2017 was announced today. The 13 books are:

- Compass by Mathias Énard (translated from the French by Charlotte Mandell)

- Swallowing Mercury by Wioletta Greg (translated from the Polish by Eliza Marciniak)

- A Horse Walks Into a Bar by David Grossman (translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen)

- War and Turpentine by Stefan Hertmans (translated from the Dutch by David McKay)

- The Unseen by Roy Jacobsen (translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett and Don Shaw)

- The Traitor’s Niche by Ismail Kadare (translated from the Albanian by John Hodgson)

- Fish Have No Feet by Jón Kalman Stefánsson (translated from the Icelandic by Philip Roughton)

- The Explosion Chronicles by Yan Lianke (translated from the Chinese by Carlos Rojas)

- Black Moses by Alain Mabanckou (translated from the French by Helen Stevenson)

- Bricks and Mortar by Clemens Meyer (translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire)

- Mirror, Shoulder, Signal by Dorthe Nors (translated from the Danish by Misha Hoekstra)

- Judas by Amos Oz (translated from the Hebrew by Nicholas de Lange)

- Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin (translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell)

Filed under Books

The Man Booker International Prize 2017: Longlist Predictions

The longlist for the Man Booker International Prize is due to be announced on Wednesday 15th March. I am on the shadow panel again this year and have been thinking about which books could make the cut.

The pool of fiction in translation published in the UK is smaller than the huge number of books which are eligible for awards like the Man Booker Prize and Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction. However, thanks to consistent championing by booksellers, bloggers and publishers helping to steadily raise the profile of translated fiction, it doesn’t actually make the predictions easier (which is ultimately a good thing, of course). I also have no knowledge of which books have actually been submitted for consideration so my choices are purely speculative. Continue reading

Filed under Books

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin

Translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell, ‘Fever Dream’ by Samanta Schweblin tells the story of Amanda, a woman who is critically ill in a rural Argentinian hospital, where David is trying to get her to remember the events which led her there. She recalls encounters with her daughter Nina and David’s mother Carla who once told her how David’s soul was split in two in order to save him after he was poisoned. However, David is not quite the same afterwards, and neither are Amanda and Nina. Continue reading

Translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell, ‘Fever Dream’ by Samanta Schweblin tells the story of Amanda, a woman who is critically ill in a rural Argentinian hospital, where David is trying to get her to remember the events which led her there. She recalls encounters with her daughter Nina and David’s mother Carla who once told her how David’s soul was split in two in order to save him after he was poisoned. However, David is not quite the same afterwards, and neither are Amanda and Nina. Continue reading

Filed under Books

3 French Novellas I Have Read Recently

‘The End of Eddy’ by Édouard Louis is a semi-autobiographical novel set in a deprived rural community in Picardy in northern France. Translated by Michael Lucey, it is a coming of age tale about Eddy Bellegueule (the author’s real name) and his life at home and at school in the late 1990s and 2000s. Eddy is gay and struggles to conform to what is widely perceived to be an acceptable type of masculinity in the small village where he is expected to go to work in the factory as soon as he leaves school. His mannerisms are routinely mocked by his peers and his family, particularly his father who even chose Eddy’s name because it sounds American and more “tough guy”. ‘The End of Eddy’ garnered lots of attention in France because Louis published his debut novel in 2014 when he was just 21 years old. However, aside from Louis’s young age and the unflinching descriptions of Eddy exploring his sexuality, ‘The End of Eddy’ also deserves acclaim more generally for articulating the reality of social exclusion in modern-day France so convincingly. Many thanks to Harvill Secker for sending me a review copy via NetGalley. Continue reading

‘The End of Eddy’ by Édouard Louis is a semi-autobiographical novel set in a deprived rural community in Picardy in northern France. Translated by Michael Lucey, it is a coming of age tale about Eddy Bellegueule (the author’s real name) and his life at home and at school in the late 1990s and 2000s. Eddy is gay and struggles to conform to what is widely perceived to be an acceptable type of masculinity in the small village where he is expected to go to work in the factory as soon as he leaves school. His mannerisms are routinely mocked by his peers and his family, particularly his father who even chose Eddy’s name because it sounds American and more “tough guy”. ‘The End of Eddy’ garnered lots of attention in France because Louis published his debut novel in 2014 when he was just 21 years old. However, aside from Louis’s young age and the unflinching descriptions of Eddy exploring his sexuality, ‘The End of Eddy’ also deserves acclaim more generally for articulating the reality of social exclusion in modern-day France so convincingly. Many thanks to Harvill Secker for sending me a review copy via NetGalley. Continue reading

Filed under Books

My Books of the Year 2016

I have read some excellent books in 2016 both new and not-quite-so-new. Here is a selection of my favourite reads of 2016:

Favourite fiction

My reading has been dominated by female authors more than ever this year. This isn’t something I deliberately set out to achieve but it is fantastic to see so many brilliant books written by women getting widespread attention. I highly recommend The Tidal Zone by Sarah Moss and The Wonder by Emma Donoghue which could be possible contenders for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize awarded to a fiction or non-fiction book about health or medicine.

My reading has been dominated by female authors more than ever this year. This isn’t something I deliberately set out to achieve but it is fantastic to see so many brilliant books written by women getting widespread attention. I highly recommend The Tidal Zone by Sarah Moss and The Wonder by Emma Donoghue which could be possible contenders for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize awarded to a fiction or non-fiction book about health or medicine.

I really enjoyed The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry which is one of the most original historical novels I have read in a long time while other recent favourites with a more modern setting include Swing Time by Zadie Smith, the Brexit-themed Autumn by Ali Smith and This Must Be The Place by Maggie O’Farrell. Continue reading

I really enjoyed The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry which is one of the most original historical novels I have read in a long time while other recent favourites with a more modern setting include Swing Time by Zadie Smith, the Brexit-themed Autumn by Ali Smith and This Must Be The Place by Maggie O’Farrell. Continue reading

Filed under Books

The Bird Tribunal by Agnes Ravatn

Translated from the Norwegian by Rosie Hedger, ‘The Bird Tribunal’ by Agnes Ravatn tells the story of Allis Hagtorn, a former TV presenter who goes into self-imposed exile from her home, job and partner after she is involved in a scandal at work. She finds a new job as a housekeeper and gardener for a man called Sigurd Bagge in the middle of nowhere despite having no real experience in that type of role. Before arriving at his isolated house by the Norwegian fjords, she expects to be caring for an elderly man but discovers on arrival that Sigurd is in his forties and is not much older than her, simply requiring some extra help in the house and garden while his wife is away. Sigurd rarely talks to Allis and has violent mood swings but she finds herself being increasingly drawn to him. Continue reading

Translated from the Norwegian by Rosie Hedger, ‘The Bird Tribunal’ by Agnes Ravatn tells the story of Allis Hagtorn, a former TV presenter who goes into self-imposed exile from her home, job and partner after she is involved in a scandal at work. She finds a new job as a housekeeper and gardener for a man called Sigurd Bagge in the middle of nowhere despite having no real experience in that type of role. Before arriving at his isolated house by the Norwegian fjords, she expects to be caring for an elderly man but discovers on arrival that Sigurd is in his forties and is not much older than her, simply requiring some extra help in the house and garden while his wife is away. Sigurd rarely talks to Allis and has violent mood swings but she finds herself being increasingly drawn to him. Continue reading

Filed under Books

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders by Soji Shimada

Translated from the Japanese by Ross and Shika Mackenzie, ‘The Tokyo Zodiac Murders’ by Soji Shimada opens with the last will and testament of Heikichi Umezawa written in 1936. Heikichi is an artist obsessed with alchemy and astrology who outlines his plans to create the supreme woman Azoth by killing and dismembering his female relatives. However, the murders he had planned in his confession are carried out by someone else several weeks after Heikichi himself is murdered in a room locked from the inside. Having baffled investigators for decades, the case remains unsolved over forty years later in 1979 until Kiyoshi Mitari and his sidekick and narrator Kazumi try to crack one of the most intriguing locked room cold cases of all time. Continue reading

Filed under Books

The Winterlings by Cristina Sánchez-Andrade

‘The Winterlings’ by Cristina Sánchez-Andrade was one of my Women in Translation Month reads in August and my rather belated review is finally here. Translated from the Spanish by Samuel Rutter, it tells the story of two sisters, Saladina and Dolores, from the small rural village of Tierra de Chá in Galicia in north-west Spain. After living in England for several years during and after the Spanish Civil War, the Winterlings, as they are known, eventually return to their grandfather’s cottage as adults in the 1950s. However, the sisters have secrets about why they have decided to come back while the villagers are equally evasive about what happened to their grandfather during the war. Continue reading

‘The Winterlings’ by Cristina Sánchez-Andrade was one of my Women in Translation Month reads in August and my rather belated review is finally here. Translated from the Spanish by Samuel Rutter, it tells the story of two sisters, Saladina and Dolores, from the small rural village of Tierra de Chá in Galicia in north-west Spain. After living in England for several years during and after the Spanish Civil War, the Winterlings, as they are known, eventually return to their grandfather’s cottage as adults in the 1950s. However, the sisters have secrets about why they have decided to come back while the villagers are equally evasive about what happened to their grandfather during the war. Continue reading

Filed under Books

‘Men Without Women’ by Haruki Murakami is the renowned Japanese author’s first new collection of short stories to be translated into English in over a decade. Echoing Ernest Hemingway’s collection of the same name, the seven tales in this collection are indeed about men experiencing loneliness and isolation without the women who are now absent from their lives for various reasons. The stories have been translated by Ted Goossen and Philip Gabriel who have both worked on many of Murakami’s previous books.

‘Men Without Women’ by Haruki Murakami is the renowned Japanese author’s first new collection of short stories to be translated into English in over a decade. Echoing Ernest Hemingway’s collection of the same name, the seven tales in this collection are indeed about men experiencing loneliness and isolation without the women who are now absent from their lives for various reasons. The stories have been translated by Ted Goossen and Philip Gabriel who have both worked on many of Murakami’s previous books. Translated from the Korean by last year’s Man Booker International Prize winner Deborah Smith ‘The Accusation’ by Bandi is a collection of seven short stories by a pseudonymous author who reportedly still lives in North Korea and works as an official writer for the government. Written in the early 1990s at a time when the country was gripped by famine, it is said that Bandi’s stories were eventually smuggled into South Korea by a relative who hid sheets of paper in a copy of ‘The Selected Works of Kim Il-sung’. While there have been many accounts of life in North Korea published by defectors, a work of fiction by an author still living in one of the most secretive countries in the world is exceptionally rare.

Translated from the Korean by last year’s Man Booker International Prize winner Deborah Smith ‘The Accusation’ by Bandi is a collection of seven short stories by a pseudonymous author who reportedly still lives in North Korea and works as an official writer for the government. Written in the early 1990s at a time when the country was gripped by famine, it is said that Bandi’s stories were eventually smuggled into South Korea by a relative who hid sheets of paper in a copy of ‘The Selected Works of Kim Il-sung’. While there have been many accounts of life in North Korea published by defectors, a work of fiction by an author still living in one of the most secretive countries in the world is exceptionally rare.  The early months of the year tend to be when lots of debut novels are plugged heavily by publishers. The Nix by Nathan Hill has been a big success in the United States drawing comparisons with everyone from Jeffrey Eugenides to David Foster Wallace and is out this month in the UK. See What I Have Done by Sarah Schmidt is another high-profile debut due in May billed as a historical murder mystery while Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders is the long-awaited first novel from the prolific short story writer and is a fictional re-imagining of events following the death of Abraham Lincoln’s son Willie.

The early months of the year tend to be when lots of debut novels are plugged heavily by publishers. The Nix by Nathan Hill has been a big success in the United States drawing comparisons with everyone from Jeffrey Eugenides to David Foster Wallace and is out this month in the UK. See What I Have Done by Sarah Schmidt is another high-profile debut due in May billed as a historical murder mystery while Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders is the long-awaited first novel from the prolific short story writer and is a fictional re-imagining of events following the death of Abraham Lincoln’s son Willie.

You must be logged in to post a comment.